|

The urbanised and industrial environment into which this generation of

Fretwell children were born and in which the majority of them grew up was

a very different place to that which their forebears had moved some years

before. Leeds was a rapidly developing, progressive city and its position

as a leading industrial centre was now well acknowledged. To complement

the more obvious fruits of this ebullience, such as the public buildings,

the community leaders now felt able to turn their attention to less

material needs. Societies for encouraging the broadening of the mind now

came into their own. Among those flourishing in Leeds in the mid-1800s was

the Philosophical Hall and Museum, which boasted a handsome theatre for

lectures, in which men of eminence were invited to lecture on the chief

subjects of science and literature. The Leeds Mechanics’ Institute had

been formed, the principal object of which was to -

…raise the intellectual character of the labouring classes, or to

establish amongst them those habits of thought and intelligence which

have since that time so greatly advanced the social and political

position of the mechanics and working classes of this and other large

towns of the kingdom.

To this period of time can be ascribed the birth of the welfare state — a

concerted, and conscious policy of State intervention to redress some of

the ‘abuses’ of the industrial system — with the introduction of a series

of Factory Acts, most significantly that of 1833, which established an

inspectorate with powers to enter workplaces, and to require evidence of

compliance with the restrictions on the employment of women and children.

This Act only applied to textile factories, but the later Acts of 1844,

1847 and 1863 extended coverage to other manufacturers.

The other side of the economic expansion equation was the inevitable

unemployment for those people whose skills had been made redundant by the

new technology. The general wave of philanthropy and evangelicalism that

typified much of the Leed’s middle class was translated into ‘good works’.

While contemporaries never used the word ‘guilt’, the clothing clubs, soup

kitchens, and charity schools were the product of a sense of duty of care

towards the labouring poor.

Free Trade principles were established by the repeal of the Corn Laws in

1846, and all remaining protectionist regulations by 1860, and by the

Navigation Acts of 1849. The impetus for removing the protection

previously enjoyed was the heavy dependence of Victorian Britain on

international trade and finance. The rationale was that the country which

diverted such a large share of its national income to overseas investment

equally depended heavily on export markets.

The crowning glory of this period was the Great Exhibition of all the

Nations which was held in the Crystal Palace. Over half of the 14,000

exhibitors represented Great Britain and her colonies, and Britain stood

out as ‘the workshop of the world’. Prince Albert, who had much to do with

the success of the Exhibition, wrote -

The products of all quarters of the globe are placed at our disposal

and we have only to choose that which is best and cheapest for our

purposes, and the powers of production are entrusted to the stimulus of

competition and capital.

It was in this dynamic environment influenced and shaped the lives of the

Fretwells of the Seventh Generation.

This section covers only the direct Fretwell line - the children of

William Fretwell. For other seventh generation offshoots of the family

refer to Fretwell Offshoots.

William Fretwell had in total twelve children - four by Elizabeth (née

Smith) and eight by Anne (née Jackson). Of these children only eight

survived beyond infancy of whom six married.

7th

Generation Spouses

| Surname |

Given Name |

Spouse of |

| Teasdale |

Washington |

Elizabeth Fretwell |

| Traun |

Bertha |

John Fretwell |

| Hartley |

Annie Marie |

Vause Fretwell |

| Elms |

Mary Jane |

Vause Fretwell |

| Hunter |

Mary Isabella |

Vause Fretwell |

| Johnstone-Lysle |

Annie Maria |

Vause Fretwell |

| Winser |

Franklin |

Edith Marion Fretwell |

| Winser |

Julian |

Fanny Emmeline Fretwell |

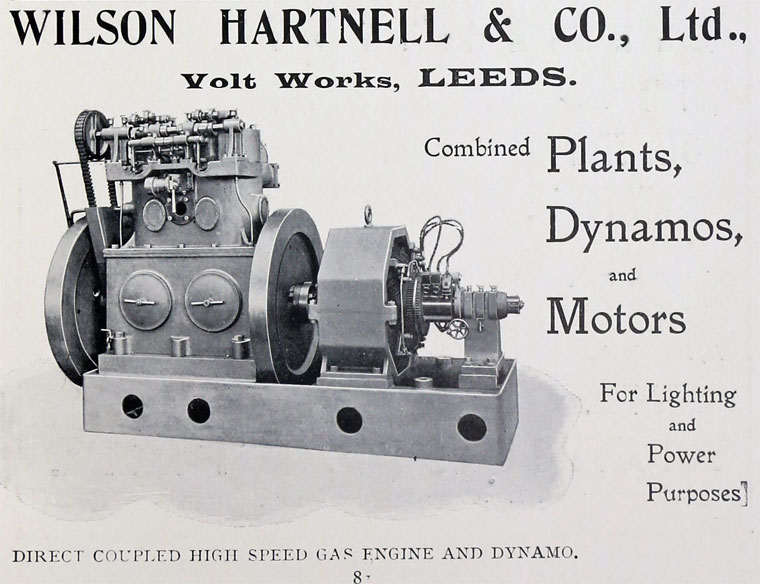

| Hartnell |

Wilson |

Florence Fretwell |

John Fretwell, great-uncle to the eight surviving children of his nephew

William Fretwell, made provision for them in his will, dated 2 December

1848, as follows.

|

To my great nephew John Fretwell the younger, son of my nephew William

Fretwell late of Leeds Grocer but now a commercial Traveller, my watch

and seal and two silver table spoons when he attains 22 years of age and

in case he should die before attaining that age then I give the same to

his brother Vause Fretwell. |

|

To my great nephew John Fretwell the younger son of my said nephew

William Fretwell my freehold messuage situate in Somers Street Leeds and

numbered 30 but in case he should die before attaining 21 then to his

brother Vause Fretwell. |

From the sale of the Talbot Estate -

|

To Elizabeth Fretwell daughter of my nephew William Fretwell £60. |

|

To all the children of my nephew William Fretwell a fourth part of the

principal moneys to arise from the sale of the Talbot Estate. |

From monies arising from the Foundry Estate -

|

To Mary Fretwell 50 shares in the Leeds & Yorkshire Ass. Co until John

Fretwell the younger attains 14 years then my Trustees shall apply the

Interest of 30 shares for the clothing and education of the said John

Fretwell and when he attains 22 to transfer such shares unto him and

also to utilize the remaining 20 shares for the benefit of Vause

Fretwell and to transfer them unto him on his attaining 22 years of age

and in the case the said John and Vause Fretwell shall happen to die

then I give 6 of the said shares to Elizabeth Fretwell daughter of my

said nephew William Fretwell. |

From the Residue of Personal Estate -

|

The residue of my personal Estate and the proceeds of my real Estate I

give to my great nephews and great niece John Fretwell the younger,

Vause Fretwell, and Elizabeth Fretwell, and the [9] children of my niece

Mary May. |

We will deal first with the children born to William and Elizabeth who

died in infancy and then follow the life of their second child, Elizabeth.

Rhoda Fretwell

The information I have for Rhoda, the first born, is as brief as her

life-span. She was born on 17 January 1828, at Leeds and died fifteen

weeks later on 29 April. There is no record in the family papers as to her

baptism, but she was buried, in the Mill Hill Chapel Yard, Leeds.

William Henry Fretwell

William Henry Fretwell was the third child, and only son, of William and

Elizabeth. He was born on 12 November 1830 and baptised, by Joseph Hutton

at the Mill Hill Chapel, on 31 January 1831 Just five years after his

baptism, and two months before his father’s remarriage, William died and

was buried on 3 February 1836. The burial service was conducted by the

Rev. Charles Wicksteed, at the Mill Hill Chapel.

Daughter Fretwell

Nothing is known about this baby daughter, the fourth and last child of

William and Elizabeth Fretwell, who was born on 13 June 1832 and died

within a few hours of her birth.

Elizabeth Fretwell

Elizabeth, second child of William and Elizabeth, although herself also

delicate, managed to overcome the traumas of childhood ailments and

survived to adulthood. She was born on 4 April 1829 and baptised later

that year on 20 September. Although she perhaps would not remember much of

her brother William, as she would only have been four years old when he

died, or her sister, born in 1832 and who only lived a few hours,

Elizabeth’s early life would not have been a happy time. She may not even

have remembered her mother who died so prematurely in 1834. There is no

account of how Elizabeth reacted to her father’s remarriage, or of her

relationship with her step-mother, Anne Jackson. For the 1841 census she

is listed with them as a 13 year old, together with her baby step-sister

Mary, living at Knostrop. Her step-brother, John, eight years her junior,

does make some references to Elizabeth in his Recollections. He describes

her as having inherited consumptive tendencies and a somewhat unhappy

disposition, but adds that he recalled her kind treatment to him in his

younger years. A further remark might also serve to confirm Elizabeth’s

possibly prickly nature, when John relates how in 1857, at which time he

was sharing accommodation at Peckham Rye with his step-sister, he spent

his Sundays -

divided between my sister at Kentish Town and my step-sister at

Peckham Rye, for although the two were both on good terms with me, they

did not like each other.

The reason for Elizabeth having moved to London was to make arrangements

for her journey to India where she was to marry Washington Teasdale who

was employed there as a civil engineer. We hear from John that the

relationship was one of long-standing.

It was a pretty old affair, for he had to make his way in India, and

even in 1857 when he could make a home for my sister, he could not leave

his duties to fetch her. So she was preparing to go out to marry him in

Bombay.

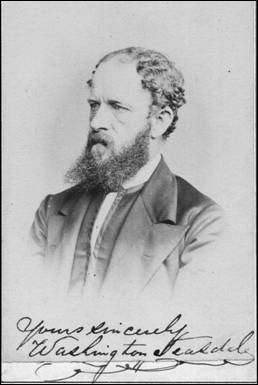

Washington Teasdale had been born at Brunswick Place, Leeds, on 8 August

1830, the first of five children born to John Teasdale and his wife Mary

(née Heaps) who had married on 29 October 1829. Washington was baptised at

the Mill Hill Chapel, Leeds, on 19 January 1831, where his four siblings

were also baptised. The Leeds Mercury of 11 February 1837 reported

that John Teasdale, aged 38 and a commission traveller of Brunswick Place,

had died on 5 February. He did not live to celebrate the birth of his last

child, John Christopher Teasdale, who was born a few months later on 19

June 1837. Two daughters - Mary Elizabeth and Mary Emily - had predeceased

their father. And so, with the death of her husband, Mary was left to

raise the three remaining children, Washington, Jane, and the baby John,

under the guardianship of their maternal grandfather, Christopher Heaps, a

prominent and highly respected citizen of Leeds. Washington was educated

at Mr. Richard Hiley's Academy, and subsequently qualified as a civil

engineer. When did Washington actually go to India? We know that

Washington was still in England in 1851, as he was listed as living at

Rosehurst, Grosvenor Road, Headingley with his grandfather (then aged 75),

and his mother Mary. Two years later, in April 1853, his grandfather died.

A notice in the London Gazette, dated 19 November 1855, stated that

the partnership between Thomas Atkinson Heaps and Washington Teasdale,

General Ironmongers, was to be dissolved due to the withdrawal of

Washington Teasdale. He was definitely in India by April 1856, as reported

in the Huddersfield and Holmfirth Examiner of 10 May 1856.

There are very many persons in this neighbourhood who will be glad to

hear that Mr. Washington Teasdale who was recently living amongst us is

now successfully pursuing a profession, for which the ability and

enterprise of this gentleman eminently fit him. By the Poonah Observer

(April 1) we notice that Mr. Teasdale is in India, on an official

engineering staff, and we may safely predict that his services are

likely to be both valuable to his country and creditable to himself. The

assistance he rendered to the cause of education throughout Yorkshire by

his personal sacrifices, will be gratefully remembered, and hearty

wishes for his welfare will be uttered by all who read this notice of

his removal from amongst us.

There were a number of ways in which the lives of the Fretwell and

Teasdale families intersected and which afforded the opportunities for

Washington and Elizabeth to become well acquainted. The most important of

these was their shared the Unitarian faith. The boys, John Fretwell and

John Teasdale were the same age, having been born just a few days apart.

Jane Teasdale, Washington's sister, was listed as a Grocer and Tea Dealer

in the 1847 Leeds Directory.

By the mid 1850s it was nothing unusual for women to be travelling to

India. However, events in India the year before Elizabeth’s planned

departure must have given her, and her family, some cause for disquiet. At

the very time she was making her preparations, reports of the Indian

Mutiny, sparked off on 10 May 1857, were reaching England, and were widely

(and somewhat luridly) reported in the national and provincial newspapers.

But maybe Elizabeth did not dwell on the potential dangers, and

concentrated more on the challenges facing her as the future wife of a Raj

Sahib, as cited by Margaret MacMillan in her study Women of the Raj.

The end and object is not merely personal comfort but the formation

of a home - that unit of civilization where father and children, master

and servant, employer and employed, can learn their several duties. When

all is said and done also herein lies the natural outlet for most of the

talent peculiar to women. And, in her miniature empire, the woman of the

Raj had many of the same problems as the men on their larger stage.

But if Elizabeth found this somewhat daunting, there was help at hand. By

the middle of the nineteenth century there were books of advice for the

novice memsahibs. The authors, usually women themselves, thoughtfully gave

lists, of enormous length, of items which should be brought out from Home.

Most of the lists - and much of the baggage - were taken up with clothes.

The sheer number and variety seems staggering today. The anonymous author

of Real Life in India (1847) recommended, among other things, 36

calico nightgowns and 36 nightcaps. Finally ready for her new life in

India, Elizabeth set out on her journey early in 1858. She was accompanied

on the journey by her future brother-in-law, John Teasdale (who himself

was later married in India to bride Elinor Pollock who, like Elizabeth,

travelled to India for the event) while her step-sister and step-mother

accompanied her as Marseilles with them. At this time most passengers for

India travelled the whole distance from Britain by boat but, to shorten

the journey, some, like Elizabeth and John went by train across France or

down through Italy to catch a steamer to Egypt. The Bombay Times and

Journal of Commerce noted, in its 9 June 1858 issue, that Miss

Fretwell had arrived from Marseilles.

John Fretwell alluded to the long engagement period. Commentators on

Indian Raj history agree that extended engagements and separations were

not necessarily the wisest course of action. As noted by Margaret

MacMillan, this was even more critical when the bride-to-be was venturing

to a country about which she probably knew very little, taken away from

her close family, and definitely out of her ‘comfort zone’.

Girls took a risk if they got engaged at Home before they had seen

India. They shrugged off the warnings about the heat, the insects, the

diseases the boredom of life on small stations. At a distance India was

glamorous: the rajahs in jewelled turbans, the elephants in harness

trimmed with gold and silver, the spacious bungalows, all those

servants. Sometimes engagements took place years before the wedding. The

men returned to India to establish themselves in their careers while

their brides-to-be waited - and waited. Not surprisingly, there were

couples who did not recognize each other when they finally met again. Or

perhaps they found that the reality was not quite so attractive as the

memory.

It is to be hoped that this unhappy experience was not shared by Elizabeth

and Washington and they married very soon after Elizabeth's arrival - on

Monday 14 June 1858 at the Cathedral, Bombay. Was it a quiet wedding or a

more lavish occasion? It was held on a Monday, perhaps suggesting a low

key affair. However we do have some account of the general way the wedding

celebrations were conducted, depending on one’s means and preferences.

Most couples got married in a church as a matter of course.

Everything was done to make the wedding as much like one at Home as

possible. Family and friends rallied around to help with the church and

the wedding breakfast…For more elaborate weddings, invitations, in

silver or perhaps white with a silver border, were sent out months

before. The champagne was ordered from France, oysters from Bombay,

tinned pâté de foie gras from a branch of the Army and Navy Stores. The

bride wore clouds of white tulle, and a veil with a circlet of myrtle or

orange blossom. If her family could afford it, the dress came from Home

or from one of the big shops in Calcutta or Bombay; otherwise the

invaluable durzi [tailor] came up with something. There would be

a white cake on a stand and a display of the presents - photograph

albums, vases, clocks, cruets, silver salvers - with which the young

couple were going to start their housekeeping.

|

|

|

Elizabeth Fretwell (c 1857) |

Washington Teasdale (undated) |

Elizabeth did not have the opportunity to practise her memsahib skills for

very long, if indeed she had ever been physically and mentally capable of

doing so. For her confinement occurred almost nine months to the day after

her wedding. We know that she did not enjoy a robust constitution, and the

fact that she had been carrying twins must of itself have sapped her

strength, even before any account is taken of the prevailing conditions,

and the climate. Childbirth itself was bound to be a frightening

experience for these women, not least because it was difficult to obtain

proper medical care. Women in the bigger cities had access to doctors,

nurses and hospitals, but those on the smaller stations had to take

whatever was available, and that usually meant military doctors…even after

the use of chloroform was accepted in Europe, doctors in India continued

to think it an unnecessary luxury.

On 22 March 1859, in the Fortress of Asseeghur, Elizabeth gave birth to

twins, a daughter Mary Eliza and a still born boy. Within two weeks after

her confinement, on 7 April 1859, three days after her 30th birthday,

Elizabeth herself succumbed from exhaustion. The deaths column of the 28

May issue of the Leeds Times carried the following notice,

signalling Elizabeth's sad end.

On the 7th ult., in the fortress of Aseerghur, India, ELIZABETH, wife

of WASHINGTON TEASDALE, Esq., C.E., and eldest daughter of Mr. Wm.

Fretwell, of this town.

Mary Eliza was taken back to England by her Uncle John Teasdale and was

there cared for by her Teasdale grandmother. She did not survive long past

her first birthday. Her death was recorded in the Leeds Times of

Saturday 28 July 1860.

On Sunday, at Rosehurst, Headingley, in her second year, Mary Eliza,

daughter of Washington Teasdale, Esq., Esq., Asseerghur, East Indies.

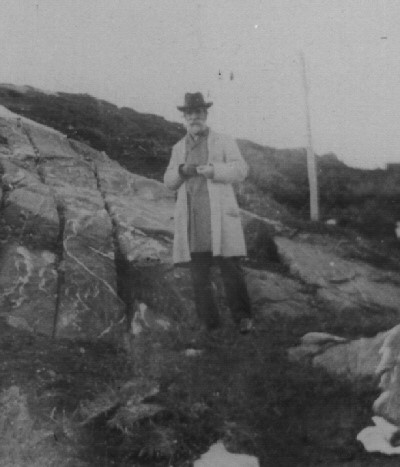

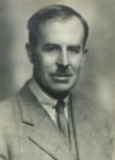

We do not know how much longer Washington stayed in India. But he was back

in England for the 1871 census, living with his mother, at Rosehurst, 5

Grosvenor Terrace, Headingley, and listed as a retired civil engineer. He

was still there for the 1881 census, by which time his widowed mother had

died, and the only other people with him in the household were two

servants, Hannah Ward and Martha Williamson. By 1891 Washington had moved

out of the family home and was, for the census of that year, living at Fir

Dene, 4 Bainbrigge Road, Headingley. He was being looked after by Mary

Turner, housekeeper. Ten years later, and Washington had again moved, to

255 Hyde Park Road, Leeds. He was then 70 years old. He had also had a

change of housekeepers, and this position was now occupied by one Caroline

Shaw. Having seen in the new millennium, Washington died in 1903 at the

Scarisbrick Hotel, Southport. He was buried at the Woodhouse Cemetery,

Leeds. He left an estate valued at £11,069 14s 9d, to be administered by

his executors – John Christopher Teasdale, accountant (brother), James

George Chadwick, cloth-merchant (brother-in-law), and Frank Kidson, artist

(close friend).

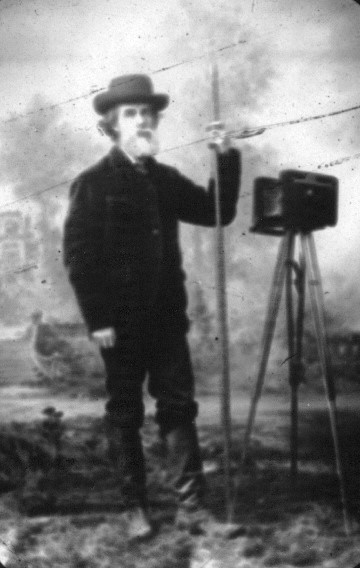

The Royal Astronomical Society journal (Vol 64, p.293) published a lengthy

obituary, covering Washington's early years and then his life from the

time he qualified as a civil engineer to his death.

When the railway system of India was being constructed, he went out

to that country to take part in its development. Here he remained for

several years, acquiring such a complete mastery over the native

language that it is said he preserved the habit of thinking in

Hindustani till the very close of his life. On his return to England he

settled in Leeds and possessing he means, and having ample leisure, he

devoted himself to the cultivation of his scientific tastes. These were

many and varied, and there was hardly any local scientific society with

which he was not connected. In particular he actively interested himself

in the Leeds Astronomical Society, the Leeds Naturalist Club, the

Institute of Science, Art and Literature, throwing himself into whatever

subject he took up with most delightful enthusiasm. Photography was an

art in which he took especial interest; indeed he was amongst the

earliest workers in his field, and in conjunction with a few friends, he

founded a photographic society before he went to India … Astronomy had,

however, the chief fascination for him. He was elected a Fellow of this

Society in 1886; he was an original member of the British Astronomical

Association; and in his native town he had a large share in the

resuscitation and the development of the Leeds Astronomical Society, of

which he was President from 1893 to 1897 … His love of science amounted

to a passion. It had for him an absorbing interest, and for the greater

part of his life was his sole occupation, and a hobby which gave a joy

to existence. His house in Hyde Park Road, Leeds, was quite a treasury

of scientific apparatus, works of art, and interesting curios, and other

subjects which denoted the wide range of his studies and sympathies…

His death took place during the meeting of the British Association at

Southport. He had gone thither to attend the meetings, and was visiting

a friend, when he was seized with illness, and remained in a state of

coma for some time. Hopes were, however, entertained of his recovery,

but a second attack followed the next day, and he died on Saturday, the

19th of September 1903, at the age of 72.

|

|

Washington Teasdale in Later

Life |

Washington Teasdale was a typical Victorian gentleman amateur scientist

whose. These were men of means who had the time and the money to invest

into their hobbies. The materials and instruments needed were expensive

and it would require extensive free time to set up and perform

experiments. The sciences they dabbled in included astronomy, geology,

geometry, microscopy, mechanics, meteorology, and photography.

How free would Washington have been to indulge in his passion as a

gentleman amateur scientist if he had family responsibilities? The

obituary makes a fleeting reference to his wife –

Mr. Teasdale married and had one child, but he survived both his wife

and child by many years.

A particular interest of Washington’s, and one for which he had gained

some eminence, was the development and use of microscopes. He was a Fellow

of the Royal Microscopical Society, and it was this expertise that was

called upon by Messrs Field and Co, Manufacturing Opticians of Birmingham,

Sole Makers of the Society and Arts’ Prize Students’ Microscopes, when

they asked Washington to write a small treatise, endorsing one of their

products. This paper, published in 1876, served two purposes. Not only did

it give Washington the opportunity to introduce the readers to the

instrument that he had designed, but it also provided some good publicity

for the stockist. This little pamphlet was entitled :

A

BRIEF PAPER

on the

USE AND EDUCATIONAL VALUE

of

SIMPLE MICROSCOPES

in general and the

Field Naturalist’s Microscope

in particular

Not missing the opportunity to talk about a subject dear to his heart,

albeit in the rather didactic and unimaginative style of the day,

Washington declared himself delighted to be:

…complying with the request of Messrs. Field & Co. that I would write

for publication some description, and directions for the intelligent use

of the cheap educational Microscope they have at my request made for

sale, and now offer to the public.

William Fretwell’s grief from the loss of three children in such a short

time span was to some degree mitigated by the more robust family that his

second wife was able to bear. Of the nine children born to this couple,

seven survived to adulthood. It is an interesting statistic that according

to social historian J.F.C. Harrison, the infant mortality rate was such in

the late 1840s that to ensure two surviving children a married couple

could expect to have five or six births.

John Fretwell

We are fortunate that John left an account, albeit somewhat ‘one-eyed’, of

his life, much of which deals with his religious beliefs, and the

troublesome Herr Ronge. Rather grandly titled

Fretwelliana

being

Fact and Fiction

from the

Life and Thought

of

John Fretwell, of Leeds in Yorks

The Lad and the Ladye

it does provide some valuable insights into his own, and his relatives’

lives and attitudes. The story of John will, therefore draw heavily upon

his own account which I have named "Recollections". This account was

written in his later life when he was living in America. Thus sums of

money are given in US dollars rather than English pounds.

John was the first child, and one of two sons, of William and Anne. He was

born on 11 June 1837 at Upperhead Row, Leeds, very shortly after his

parents’ first wedding anniversary. It was three months later that he was

baptised, given the family name John, at the Mill Hill Chapel, the Rev.

Charles Wicksteed officiating. John’s early life was spent in Yorkshire.

In a very neatly set out letter, to his paternal Grandmother Mary Vause,

written at Selby and dated 12 December 1849, John, aged 9, reported on his

and his brother’s and sisters’ educational progress.

My dearest Grandmother,

As I and my Brother,

Have a holiday granted to day

I cannot do better

Than to write you a letter

To please you is better than play

I am sure you will hear

With pleasure sincere

That I and Vause are improving at school,

In accounts I’m as far

(Though some hard tasks there are)

As Decimal Fractions, first rule

I am now learning Latin,

But of myself to keep chatting,

Will make you fancy me full of conceit,

So now let me tell

That Mary spells well

And Alice the Alphabet tries to repeat

As Christmas is near,

Now Grandmother dear

Your company we hope you will give us

And dear Uncle will come,

To meet him we’d run,

He was always so very kind to us

In the hope you will come

Believe we all join,

And at the Train my Mother will meet

You with a coach,

Of one Selby can boast,

So pray don’t refuse us the treat

I hope you are well,

And that Uncle will tell

When he writes, (which I trust will be shortly)

That Rheumatic pangs

Have not seized your hands,

Which would indeed grieve us most heartily

Unto Uncle and you

I must now say adieu,

As my lessons I still have to get well,

Believe me to be

In truth and sincerity

Your affectionate Grandson,

John Fretwell

The 1851 census records John as a boarding pupil at the Yeomans’ School,

Lord Mayor’s Walk, in the St Giles area of York. Why the choice of school

away from his home town? The Yeomans' School specifically catered for the

sons of families from what may be described as the lower-middle class.

John was enrolled there at a time when his parents were facing financial

difficulties, and moving houses, and he may have either lived or stayed

with at his maternal grandmother’s house at Selby and also with his

step-sister during the holidays as he makes reference to the latter's

kindness to him during his schooldays.

As the eldest son it seems that John was destined for the grocery trade.

In September 1852, just after his fifteenth birthday, young John was taken

by his father to London to begin his apprenticeship with Wall, Smith and

Co, of 103 Saint John Street, West Smithfield. It was not a career, in any

other circumstances, that he would have chosen for himself. As was to be

confirmed later, he was temperamentally and intellectually unsuited for

the commercial world, being far more drawn to matters religious. The move

to London was :

… in direct opposition to my personal inclinations, for while my

Father was a Unitarian, I was strongly attached to the Anglican Church,

in which my mother was born and bred; and could I have followed my own

desires, I should have prepared myself for the ministry of that church …

But my Father, I now think, made a better choice for me than at that

early age I should have made for myself. It was certainly the best he

could make, with due regard to his own conscience and means; and I doubt

if any parents in their position could have done better for their son

than mine did.

Thus the dutiful, if reluctant, son left home to prepare himself for his

future career, and he certainly applied himself to the task over the next

few years.

John gives an enlightening account of life as an apprentice. For the first

two years he lived in his employer’s house, giving his services for his

board and lodging, and, he says, though he hated the business, he became

very much attached to his employer and gained his confidence. Initiation

was evidently a prescribed rite of passage for new apprentices for John

recounts a very early experience of his life in London.

On my first Sunday there my fellow apprentices had taken me on a long

walk to Jack Straw’s Castle on the Heath, where certain mystic rites,

common among the ‘prentice lads of those days, were indulged in at my

expense.

The working day of an apprentice was protracted, beginning at 7.00am and

ending at 6.00pm. Apart from the long hours, John reports that his

business indeed had another very serious objection. In order to succeed in

it, it was necessary to acquire a reputation as a good judge of the

quality and value of teas and coffees. This could only be done by tasting

their infusions, and in a large business, many hundreds of samples were

tasted daily. The unfortunate effects of which were that :

This makes the tasters extremely irritable, and many of them indulge

in quantities of tobacco, alcohol, or other narcotics, to counteract the

excessive nervous irritability induced by the abnormal consumption of

tea and coffee. This I did not do, and so became very excitable, and was

often warned that I ought to leave the business or devote myself to a

less lucrative part of it.

For the first two years of his time in London John did not see his

parents, for the rule of the business house to which he was indentured was

that holidays were only given once in two years. But not all contact was

lost with his family, and John seems to have been relatively contented and

free to follow his extra-mural interests.

But I was in receipt of regular letters from home. My superiors in

the office, though very fond of pleasure, were very thoughtful and

gentlemanly, and never interfered with my free employment of my leisure

and I led on the whole a happy life.

As with many young men of the time, John’s formal education had finished

on reaching his 15th birthday. Unlike the more frivolous

superiors referred to above, John’s time after work was spent in study. No

doubt he was motivated by a need to get on in life, and this was coupled

with a life-long enthusiasm for learning. He spent his evenings at Crosby

Hall, an Anglican establishment, where various clergymen gave their time

to teaching young men who, when their day’s work was over, went there for

self-improvement. Indeed, John still harboured hopes of being accepted

into a theological course and then entering the Anglican ministry and to

assist him his mother offered him money she had saved from her household

allowance. On the other hand he was given no encouragement from his father

who was staunchly Unitarian. Besides, as John fully realised, his father

was now 60, had lost all his money, had no life insurance, and if John was

to enter the ministry, who was to provide for the younger Fretwell

daughters in case of his father's death?

What John describes as the first important change in this life occurred in

1854 when his employer decided to get married, and needed the run of the

whole house that he and John and shared. John was therefore obliged to

find his own board and lodgings. To assist with this, his employer now

paid John $300 a year, which he found, with care, amply sufficient for all

his necessities. John was fortunate to find lodgings, about 35 minutes

walk from his work, with the family of Mr. and Mrs. Dalby, who were from

Yorkshire, and who were distantly related to his step-sister Elizabeth.

The Dalbys were to have considerable influence over John, and maintained

an abiding interest in his progress and family. From them John

… learned how much high thinking was compatible with very plain

living.

John formed a particular bond with Mrs. Dalby.

Especially valuable to me was the intercourse with Mrs. Dalby. Since

leaving my mother’s house I had no female intercourse at all, and while

my male associates were of the best, the influence of a well bred and

experienced woman is of inestimable value to a young man.

John’s interests broadened during his time with the Dalbys. He continued

with his evening studies at Crosby Hall, but now also music and the drama

began to take some place in his recreations. Through reading aloud with

the family he learned to appreciate the works of Sir Walter Scott and

Shakespeare. But, most significantly, it was through accompanying the

Dalbys to their chapels and meetings that John gained a better

understanding and empathy with Unitarianism. A reading of the

Recollections will provide a clearer and fuller exposition of John’s

religious affiliations, and I do not want to dwell too much on them here.

However, it is important for understanding John’s character, and the path

he took in later life, to have some comprehension as to his religious

‘quandary’. Though he finally wholeheartedly adopted the Unitarian faith,

it was not a decision made without much soul searching and almost with

some sense of regret.

My teachers at York Diocesan School … and other Anglican Ministers

who taught at Crosby Hall ... and other Anglican lay and clergymen under

whose temporary influence I came at the Working Men’s College in Great

Ormond St. were all, so far as I could see, true incarnations of the

spirit of Christianity, and to their church many of my best friends

belonged. They have done me much good, and no conscious wrong. Both my

interests and affections held me firmly to them.

And if that other influence of my Father’s, beginning so quietly yet

effectively in holiday time, strengthened by my desultory reading in his

library, and made thoroughly clear to me by those historical studies

with Dalby, or the guidance of Ierson’s preaching, had finally led me to

believe that the ethical and intellectual balance was in favour of the

Unitarian argument, it was in no spirit of revolt, but with infinite

sorrow that I renounced the notions of my early life.

It was during his stay with the Dalbys that John first began to teach in

the Unitarian Sunday School, and work voluntarily with the associated

Domestic Mission, which sought to spread religious and moral influences

among the very poorest people of London. The branch of the mission to

which he was attached was located in Spitalfields, a wretchedly poor part

of the East End of London, originally settled by Huguenot silk weavers. He

describes them with some admiration.

They were miserably poor, seldom earning more than $4 a week, but

they were far more temperate and economical in their habits than the

people of English and Irish descent among whom they dwelt. Their garret

homes were clean and neat, and often adorned with flowers … On Sundays

they would often wander far into the Epping Forest and the Woodlands

beyond the Lea, botanising and collecting insects, and I learned in

converse with them to appreciate the meaning of John Milton’s ‘Spare

fast, that with the Gods doth diet’.

In his nineteenth year John was pleased to report that the previous two

years of his life had been rewarding and that he was generally happy with

his lot.

I was busy all day as the confidential clerk of Wall, Smith and Co,

who after 5 years experience, trusted me thoroughly…I was working hard

in business from 9 till 6. By early rising in the summer I secured time

before breakfast for my studies. In the evening I was either among

fellow students at Crosby Hall, or teaching in the domestic mission. My

Sundays were divided between the chapel and the school, and at the

morning and vespermeal enjoyed the society of Mr. and Mrs. Dalby, who

treated their lodger as though he were a younger brother. My noonday

meal consisted generally of bread and cheese and a few raisins and a

glass of water.

As well pursuing his studies, John was also called upon as a lecturer at

Crosby Hall, and had the honour to deliver the inaugural lecture in the

newly formed class in Political and Social Economy, as reported in the

London City Press of 14 November 1857.

The lecturer, after defining the nature and objects of the science,

and urging the importance of a more extended acquaintance with the

principles which regulate the phenomena of industrial and social life,

stated, that the object of his lecture was to give such an outline of

the science as might form a plan for the future studies of the class.

This summing up gives no indication of the watershed that the year 1857

was in John’s life for in that year his future became embroiled with Herr

Ronge, a German exile who established the first kindergarten in Britain at

Hampstead, London, in 1851. This meeting heralded years of difficult

situations for John and his family, but, on a happier note, it was through

Ronge that he met for the first time the young girl who would eventually

become his wife. Their first encounter was at Ronge’s house, Grove House,

Upper Kentish Town, and was a source of embarrassment to them both.

Ronge took John into a room in which two ladies were practising their

singing. The first did not impress John at all, but the second, younger

singer did catch his attention.

The second voice, a full and rich mezzo-soprano, much more reserved

in expression was sung by a slight girl about 18 years old. I am no

critic in music, having since leaving York only sung for the purpose of

keeping my voice in order for public speaking; but the impression made

upon me by this girl was more like that of watching a lark, the sound

seemed so unforced and yet so tuneful, and so full in proportion to that

little body whence it issued, that I could hardly understand how so

small a person could manage so well to harmonize with the shrill first

voice.

John reports that, when the song had ended Ronge clapped his hands and

laughed, evidently enjoying more the discomfiture of the ladies at having

sung unwittingly before a stranger, than appreciating their performance.

In turn, the ladies were evidently not pleased that a stranger had entered

unheralded. Notwithstanding his untutored musical appreciation, John had

no portent, at this time, of any romantic attachment to the younger

singer.

Who was this slip of a girl with the delightful voice? Bertha Traun was of

German stock and with her marriage to John began a German/English

inter-relationship that carried through for the next three generations of

Fretwells. The Meyer family with which the Traun and Fretwell families

were to become linked was well established in the commercial world of

Hamburg, with connections also in America. Chief architect of the Meyer

fortunes was Bertha’s grandfather Heinrich Christian Meyer (1797-1848). He

and his wife Agathe Margarethe (nee Buesch, 1794-1833) had eleven

children, of whom Bertha Traun’s mother, also called Bertha, was the

second born child.

|

|

| Heinrich Christian

Meyer |

Agathe Margarethe Buesch |

Bertha Meyer, John’s future mother-in-law, was considered quite a beauty

as the photograph of her as a young woman will confirm. Bertha Meyer

married, Christian Justus Friedrich Traun (1804-1881), another well-heeled

Hamburg businessman, known by the family as Friedrich, on 31 July 1835.

They had four sons and two daughters, the younger of whom they named

Bertha, after her mother. She was born on 27 December 1839, and baptised

at St Catharinen, in Hamburg.

At some stage in the marriage Bertha senior had become attracted first to

the religious teachings of Johannes Ronge, and then to the teacher

himself, with the resultant estrangement from and, amid great scandal,

subsequent divorce from her husband. Around 1848 Johannes Ronge and Bertha

Traun left Germany for London where, when the divorce was finalised, they

were married on 5 August 1851. The April 1851 census shows that they had

already set up house, as man and wife, living at 11 Pratt Terrace, St

Pancras. Johannes' occupation is given as author. Bertha’s two daughters,

Agathe and Bertha Traun, came with her, leaving the sons with their

father. (Agathe, who died aged 17 before John knew the family, was buried

on 10 April 1854 in Highgate Cemetery, her grave marked by a simple white

marble obelisk, with the plain inscription ‘Agatha Traun, von ihren

Freunden'). There followed a constant custody battle between

the parents Friedrich and Bertha for their children, even with some fears

(not unfounded) of attempts to abduct the younger Bertha and take her back

to her father. Subsequently, according to John Fretwell, Herr and Frau

Ronge had a child of their own whom they named Marie.

But back to the prospective groom and bride. Towards the end of his life

John described Bertha as she was when he first met her.

She was as quiet and reserved in her intercourse with me as with all

strangers. The circumstances of her early youth had made Miss Traun

serious and reserved to such a degree that English people who knew the

German tongue made this the occasion of a pun upon her name (Miss Traun

– Misstrauen, or distrust).

If Bertha was not encouraging, John did not see himself as being

particularly eligible.

Nor was a person like myself likely to attract the favourable

attention of a girl of 18 years.

I had always worked to the very limit of my powers, and therefore in my

hours of rest, had not the high spirits common to my age. I was

economical to the extreme in matters of dress and toilet, in order to

save money for my literary tastes and for my sister and accustomed only

to seek the good will and esteem of men who were occupied with the most

serious problems of actual life; I never devoted the slightest thought

to making myself agreeable to any young women but those of my own flesh

and blood, and not over much to them. If I continued the singing lessons

commenced when I was a schoolboy at York, it was only for the sake of

strengthening my naturally weak voice for the purpose of public

speaking. I never sang a song. Though I had learned to dance at York, I

had imbibed Lord Chesterfield’s idea, that dancing was a thing for

actors and not for gentlemen. My thoughts too were far too much absorbed

in serious questions as to securing my own future and that of my

sisters’ to permit any question of love. In short I was a prig.

A fuller account of their courtship is given in the Recollections, and is

here only set out in brief. Owing to the death of a son, Mrs. Ronge

(formerly Mrs. Traun) and Bertha returned to Germany, and were away from

England for some time. During that absence John and both Berthas kept in

touch by letter or by messages delivered by mutual friends and

acquaintances. During this period John actually moved in with Johannes

Ronge, at Bertha senior’s request, to keep an eye on the older man.

Meanwhile John was able to put all family matters into the background of

his mind.

None of these events or persons interfered with the steady course of

my work and study. My principals again increased my salary and I again

took a prize in the Society of Arts examinations, this time in political

economy, while I pretty well read through the German books in Johannes

Ronge’s library.

The year 1858 was one of change and challenge for John. Mrs Ronge, in

appreciation of John’s ‘guardianship’ of her husband, invited John to

spend a week in Hamburg at her expense, and made arrangements for him to

stay with one of her relatives, Ernst Conrad Meyer, in the Bankstrasse. In

the midst of planning for this trip John, having decided that it was time

to look for another position which would give him more opportunity to

sharpen his commercial cut and thrust, had handed in his notice to his

employers and had secured another position, which he would take up on his

return from Hamburg.

Judging from John’s self-deprecatory remarks on his appearance on setting

out for Hamburg, it can be surmised that the relationship between Bertha

and himself had warmed, perhaps through the encouragement of Bertha’s

mother. In John’s own words:

I certainly was nothing like a man that would a wooing go when I

started out on that journey…The very clothes I wore had been made to fit

my younger brother … He was something of a dude, and I must have looked

more ridiculous in his clothes than in my ordinary economical and

careless apparel. Having no trunk but an old sea chest, the legacy of my

sailor uncle Fred, I had borrowed a lighter, but dilapidated trunk of

Johannes Ronge. My sister Mary proposed to accompany me to the Tower

Wharf, whence I had to take a wherry [a light rowing boat used for

carrying passengers and goods on rivers] for the Hamburg steamer. It was

early in the morning and the omnibus had not yet begun to run. To save

cab hire I proposed to walk the 3 miles. So I took the trunk on my

shoulder. When Mary saw me -

‘Oh John’ she said ‘you surely are not going to walk through London in

that fashion.’

‘I surely am,’ I replied.

‘Well, then,’ said she, ‘you may go alone for I will not be seen in

London streets with such a figure as you are.’

Having suffered the rigours of steerage class (a self-imposed financial

stringency) the miseries of sea sickness and the humiliation of having

been duped by a confidence trickster, John arrived in Hamburg. This was

John’s first visit to a foreign country so, once ensconced in his

lodgings, he set out to see the sights. Also on the agenda was a reunion

with Bertha Traun and, more daunting, a first meeting with her father.

From the former he received a cordial unaffected greeting, and was

relieved and surprised with Herr Traun’s initial welcome (though alluding

to less happier future meetings).

His smile gave a singularly pleasant expression to his countenance,

and he was too polite to meet strangers with the frown that I had often

enough to brave in later days.

However, it became immediately apparent to Herr Traun that young Fretwell

had an eye for his daughter, and the relationship turned instantly frosty.

John afterwards learnt that Herr Traun had, on that very day of their

first meeting, given instructions to prevent the chance of a tête-a-tête

between his daughter and the young Englishman with an inkspot on his

collar. Such obstacles notwithstanding, on the last day of his stay in

Germany John was able to spend time alone with Bertha and, almost

surprising himself, proposed marriage.

The gold circlet, which like German husbands I still wear, bears the

date 10th September, 1858.

But some time was to elapse, and numerous hurdles to overcome, before the

pair could get married. Immediately on his return to England John took up

his new position with Hill, Son and Meadows, shipping agents of Milk

Street, Cheapside. He certainly found there a more aggressive business

ethos, but not one that sat comfortably with his personal code of ethics.

The firm had made a composition with its creditors of 25 cents on the

dollar; in itself surprising enough to a Unitarian, who regards anything

under 20 shillings in the pound as damnable heresy. In what is here

called smartness, they could have given points to the smartest Yankees I

ever knew, and won the game. I began to think that now I understood why

my former principal did not make money. He would have resented the

insinuation that he should adopt the practices of this house as a mortal

affront. Not that I would call them dishonourable. Perhaps he was behind

the times; certainly they were all but ahead.

John also wrote formally to his future father-in-law requesting his

daughter’s hand in marriage, and requesting permission to correspond with

her (she was still in Hamburg) until such time as he could provide a home

for her and thus embark upon married life. Whether to ensure that his

son-in-law would be able to provide adequately for his daughter, whether

to encourage John to move to Germany to work and thus enable the father to

see more of his daughter, or whether, as John suspected, to ensnare him

into being financially dependent upon his father-in-law, Herr Traun sought

ways of establishing John in business in Germany. This offer came at a

propitious time, because within a few weeks, John had decided that he

could never be happy working for his new employers. He gave notice, and

left in November 1858 to pursue options in Germany, armed with what he

called the wealth of commercial experience he had acquired in the previous

six weeks. Before leaving he was able to fit in a quick visit to Leeds to

his parents and to announce the good news of his betrothal.

The business opportunities offered by Herr Traun were either to manage a

chemical company or to work for an insurance agency. John was both bemused

and alarmed, as he felt that his qualifications and experience left him

ill equipped to undertake either of these ventures. Tactically he was at a

disadvantage, money being just one factor. He had expected to, but never

did, receive unpaid wages from Hill, Son and Meadows, and he did not wish

to antagonise, any more than could be helped, the man whose daughter he

wanted to marry.

No business agreement was reached between John and Herr Traun, and in the

interim John devoted his time to those studies which might help him in

German business and in mastering the details of commercial work. By early

1859, with no resolution to the situation, and no doubt with tensions

rising between the two men, particularly as it appeared that Herr Traun

was intent on thwarting the marriage, John decided to return to England

with the avowed intention never to settle in Germany. He had, in any case,

another reason to return as he was about to come into his inheritance left

to him by his late great-uncle John Fretwell on his 22nd

birthday which fell in that year.

John was fortunate that his first employers were prepared to take him

back, and to pay him a sufficient salary. Maybe the tea and coffee

business was more to his liking than before, in view of his recent

experiences. But overall, 1859 was not a happy year for John.

First, Bertha called off their engagement (although, strangely, she does

not appear to have advised her father of this, as he continued to canvass

business opportunities for John). Second, possibly as a consequence of a

depletion of his physical reserves, John fell victim to the small pox

epidemic of autumn 1859. He was seriously ill, requiring him to take five

months off work to recover. The attack of small pox apparently left him

badly disfigured, of which he was very sensitive. He was most fortunate

that his employers continued to pay him in full during the recovery and

convalescence. However, his convalescence would have been speeded up by

Bertha’s decision to resume their engagement.

John himself refers to the strain of overwork and anxiety, and ascribes

the period from December 1858 to March 1861 as contributing to the onset

of his ‘head trouble’, a cure for which he did not find until he went to

America later in life. There is some confusion as who actually called off

the engagement as John also claims that as an honest man he could not, in

conscience, undertake to marry Bertha until he had determined whether the

affliction was temporary or permanent. Therefore he had written to her

suggesting a postponement of the marriage. However he regained his health

sufficient to assure himself that the marriage should proceed. (If the

‘head trouble’ was migraine, it is interesting to note that this

affliction has continued down through the male line to the current

generation).

Once more Herr Traun had a proposition for John, and now that the

relationship with Bertha had resumed, it seems that John was ready for

some serious negotiating. The business ‘on offer’ was in Lippstadt, and

from the first inspection, John had strong reservations about its

potential and its location.

A more unattractive place to commence life in, or a less attractive

business for a man of my tastes could hardly be conceived. [The

customers were mostly Jews or Papists, a large part of the business was

in what are called religious articles for Roman Catholics]. The

customers of the business were the petty nobility and gentry of the

neighbourhood, an altogether contemptible set of people, or Jewish and

Roman tradesmen. There was a ropery connected with it, where twine and

cordage were made by hand. About $15,000 were necessary as capital and I

had only about $3,000. The country belonged to the kingdom of Prussia,

but the sympathies of the Roman Catholic population were mostly with

Austria, which then had a terribly bad influence on the German people.

Haggling over the financial arrangements of the deal between the vendor,

Herr Traun and John continued without any satisfactory resolution. It was

time for decisive action, and John, in a move quite alien to his

character, confronted Herr Traun with an ultimatum, the setting for the

drama being the Leipzig Fair of 1860. Having first received Herr Traun’s

assurance that he had no objections to John as a son-in-law, John launched

on what was probably a well rehearsed speech.

He must have seen, I continued, that his daughter’s preference for me

was no mere girlish fancy, since it had withstood the temptations of all

the luxury with which he had surrounded her and even the repulsive

ugliness of my pock-marked face. She had just written me that she would

follow me to China if I called her there. If he thought she was likely

to give me up, well and good. I would abide by the result. But so long

as she preferred my poverty to his luxury, I proposed to fight for her

to the bitter end. I could, I said, earn more by my own exertions in

England than all his help would bring me in Germany, and I preferred to

do so. I would not undertake a single obligation that my own small

capital would not cover. It was his affair not mine, if he insisted on

my undertaking a business requiring more.

And John then delivered the coup de gras.

I would not, I said, undertake any business at all in Germany, unless

he published notification in the Hamburg papers that F. Traun of Hamburg

had the honour to announce the betrothal of his daughter Bertha with

John Fretwell the younger of Leeds; and that as to money matters, he

might do what he liked, and I should do what I thought prudent.

John set a deadline of that same afternoon for a response. It would seem

that his boldness had paid off.

He promised me that if I would undertake the business in Lippstadt he

would consent to the immediate publication of our betrothal and to our

marriage a year later, and he would put into my hands $10,000, no part

of which was to be repaid within 14 years even if we did not marry, and

if we did, it was to be his daughter’s dowry, and that at the end of the

Fair he would bring his daughter to see the place before I decided on

staying there.

But, as John ruefully noted later, Herr Traun’s response was not given in

writing. While John kept his side of the bargain by determining to make

the best of the Lippstadt business, and to prepare for Bertha to join him

there, Herr Traun found a number of excuses for delaying the announcement.

Finally, however, it was made official with the following notice in the

German papers.

Bertha Traun

John Fretwell

Verlobte

Leeds : Hamburg

A great party was held at Rothenburgsort, the Traun summer residence and

there, in the presence of all the family, John and Bertha exchanged

betrothal rings. As John comments:

There might be many a slip twixt cup and lip, but I had gained one

decisive battle on the enemy’s ground, and now I went back to Lippstadt

to prepare for the next.

There were still a number of formalities to be completed, including

obtaining permission from John’s parents for him to wed. This is

surprising since John was now in his 23rd year, past the age of

majority in England which at that time was 21. However, in Germany the age

of majority was 24, and this may be the reason for obtaining parental

consent. The declaration, in duplicate, signed by William and Anne

Fretwell and witnessed by John’s sister Mary, and Ishmael Lythgoe,

Manchester Town Clerk reads :

We the undersigned William Fretwell and Anne Fretwell of 4 York

Terrace Whalley Range Manchester, in the County of Lancaster England do

hereby declare that we consent to the marriage of our Son John Fretwell

jnr now residing in Lippstadt Prussia, with Miss Bertha Traun of

Hamburg.

Manchester

April 2nd 1861

On the basis of this declaration:

In Faith and Testimony whereof

I, the said Mayor, have caused the Seal of Mayoralty of the said City,

to be hereunder put and affixed, and the Certificate of Consent

mentioned and referred to in the said Declaration to be hereunto

affixed.

Dated at Manchester, the second day of April in the twenty fourth year

of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, and in the year of our Lord

1861.

Matthew Curtis

Mayor

Proof of John’s baptism was also required. With two copies of the original

baptism entry, the following letter was furnished. The signatory was James

Kitson, then Mayor of Leeds, and the great-grandson of Mary Fretwell, who

had married Richard Kay (and thereby second cousin once removed to the

groom to be):

Borough of Leeds in the Country of York

To all whom these Presents shall come, I, James Kitson, Esquire, Mayor

of the Borough of Leeds, in the County of York, in that part of the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland called England, In pursuance

of the Laws in that behalf, do hereby certify that on the day of the

date hereof, personally came and appeared before me Thomas Hincks

[Minister of the Mill Hill Chapel], being a person well known and worthy

of good credit, and who did before me solemnly and sincerely declare the

two several documents hereunto annexed marked respectively with the

letters “A” and “B” to be respectively two copies from the Register of

the Book of Births and Baptisms kept by the Minister of Mill Hill

Chapel, in the parish of Leeds aforesaid.

In Faith and Testimony whereof, I, the said Mayor, have caused the

Corporate Common Seal of the said Borough, to be hereunto put and

affixed, and the said Documents to be hereunto annexed. Dated at Leeds

aforesaid, the Twenty Sixth day of March, in the year of our Lord, one

thousand eight hundred and sixty one.

The year following their engagement, some four years after they had first

met, John and Bertha were married. The ceremony was conducted at the Traun

summer residence and a notice placed in the newspapers in July 1861,

announced the event to the world.

On the 9th inst. at Hamburg, by the Rev. Dr. Alt,

Mr JOHN FRETWELL, of Lippstadt, Westphalia, eldest son of

Mr William Fretwell of Whalley Range, Manchester, to

BERTHA, only daughter of FRIEDRICH TRAUN, Esq. of Hamburg

Traun Residence, 1861

In John’s words:

At last I was enabled to take Miss Traun from his [Ronge’s] House to

that of her Father and there, on the 9th

July 1861 we were, after so many conflicts, happily married by the

senior pastor of the Hamburg Lutheran Church, Senior Alt, in the

presence of the Father and Mother of my wife, her brother, her uncles

Heinrich and Adolf Meyer, and their wives.

John, never one to wax lyrical, gave, for him, an effusive account of

their honeymoon. The tone indicates that, for the present, he and Bertha

were a very happy couple.

But to return…to our own little heaven. We drove off along the Elbe,

and past the factory of my Father-in-law, where the Union Jack floated

alongside of the 3 towers of Hamburg, then across the Ferry, and through

the Farms of Wilhemsburg, again were ferried across the Southern Elbe,

and then by rail through the Lundburger Heide till we halted where my

mother-in-law had spent the first year of her unhappy marriage at

Hanover. But soon we left that behind us and were in the land of

romance—the German Harz; in the old imperial palace of Goslar; down in

the silver mines of Klausthal, where the miners working in their old

fashioned way reminded one of the gnomes with which folklore peoples the

whole district, then on the Brocken, where Goethe’s Faust saw witches

dance with Mephistopheles, or amid the elfin dwellers of Rübeland. And

so we drove through this wonderful land of legend, taking our carriage

when we were tired, at other times losing ourselves in the woods, or

walking over the hilltops sending the coachman round to meet us at some

distant spot, living in the recollections of hoary antiquity, and an

ever-present heaven of our own. After a fortnight of this travel we sent

our German coachman back to Harzburg, and took the rail for our future

home at Lippstadt.

And Lippstadt, Westphalia, seemed to take on a difference perspective now

that John had his wife by his side.

Lippstadt, a place of 6,000 inhabitants, had more educated people in

it than an American town of the same size would have. The officials at

the law courts, the teachers at the high school and the medical men of

the place, were all university men of wide literary culture. And my

sweet wife won all hearts, though, after all, we were enough for each

other.

By all accounts the first months of their married life, and the business

in Lippstadt went smoothly But this peace was not to last. First, at the

behest of his wife, John returned to England to sort out the financial

mess left behind by Johannes Ronge, when he returned to Germany in 1861,

under the amnesty for religious dissidents. On his return John brought his

fourth sister Fanny to stay, and she remained with the family until he and

Bertha eventually returned to England. The effects of this interruption on

John’s business were heartfelt, and the following, recounted later to his

own son, indicates clearly the fragility of his relationship with his

staff.

Hardly had I returned to my work in Lippstadt, when your mother

demanded of me that I should leave my business, go to London, and clear

up the Augean Stable that Ronge had left there. Willing to render any

sacrifice to help your Grandmother [Anne Fretwell], I went, and did so,

but for every dollar that I saved your Grandmother I lost more than a

dollar for myself; you can well understand what it means for a man to be

absent fourteen days from a business such as mine was in Lippstadt, what

thousands of dollars worth of stuff can be stolen without the slightest

possibility of detection, unless one can rely implicitly on the clerks,

and how could I, a stranger in Prussia, do this?

However, despite his fears, after this visit to England John reports that

he had six months of quiet domestic life, and was kept very busy with his

business affairs. But Bertha’s family soon intruded again, and, in what

was to be a continuing pattern, Bertha left John for an extended period to

care for her mother, returning to Lippstadt in 1862, only to be recalled

once more to her mother’s sickbed. Apparently, Frau Ronge suffered bouts

of what was diagnosed as "Hysterische Frauenzimmer". This time she did not

return until after her mother’s death in April 1863. For the first three

years of their married life Bertha was ‘absent’ staying with her own

family - in 1861 at Alte Teschenstrasse, Breslau; in 1862 at 27, Oederweg,

Frankfurt on Main; and in 1863 at 8 Obermainstrasse, Frankfurt on Main.

This is an appropriate point to take a look at the children born to John

and Bertha. But we cannot rely on any detailed account of these events

from the father for, while John wrote in considerable detail about his

religious beliefs, and his business affairs, and the troublesome Ronges,

there is only one reference in the Recollections and the Supplementary

notes to the birth of any children - the first born, Freddie. There is no

reference to the early deaths of this first son, nor to baby John, and

nothing said about the still-born son. It is not until much later that

John makes any reference to his only daughter Emmy. Bertha’s family

duties, and the frequent periods of separation, probably accounts for the

fact that it was not until after her mother’s death that their first child

was conceived. Thereafter over a period of seven years, four more children

were born, of whom only two, Emmy and Ralph, survived to adulthood.

|

21 May 1864, Frederick Dalby Fretwell, Lippstadt, Westphalia |

|

29 Sep 1866, John Fretwell, London |

|

17 Apr 1868, Emmy Hilda Bertha Fretwell, Hackney |

|

8 May 1870, Ralph Traun Fretwell, Hackney |

|

16 Jul 1871, unnamed son, Hackney |

The years immediately following the birth of son Frederick were a time of

upheaval - in every sense - as once more Bertha left John to go and stay

with her father, leaving John to carry on, and then liquidate, the

business. It was during this time that he was admitted into the local

Westphalia Masonic Lodge, and may have been the first of the Fretwells to

join the freemasons.

And clearly things were awry. John alludes to this period in his notes to

Ralph, and in so doing makes reference to his faith, which, more and more,

was to become the focus of his life.

Even before the birth of your Brother my married happiness was

sacrificed by her [Ralph’s mother]…I sought and found in my Unitarian

faith some substitute for that which I had hoped in vain to find in my

life with your Mother.

Notwithstanding, John was able to extricate his wife from her family, and

by 1865 they were living at 8 Upper Homerton Road, London NE. Frederick

was baptised on 3 December 1865 at the Unitarian Church by the Rev. Robert

Brook Apsland. It was at Upper Homerton Road that son John was born, and

died two hours later, on 29 September 1866, the death being due to his

premature birth as reported to the registrar by father John.

For the 1871 census the Fretwells were recorded as living at Downs Lodge,

Downs Road, Hackney. John was listed as a 33 year old Merchant. Bertha and

son Frederick Dalby had become naturalised British subjects. A nurse,

Elizabeth Overley, was employed to assist Bertha, who would have been

again pregnant. The rest of the household comprised children Emmy aged 2

and Ralph Traun aged 10 months, Hannah Saunderson, housekeeper, Jane

Greaves, domestic servant, and Rebecca Barrett, cook. The family stayed in

London until about 1873, moving once more in that time to 37 Evering

Villas, Amherst Road, Hackney. Ralph also records that his own mother was

severely ill in 1870 and in November of that year went to convalesce at

Dallon House, Broadwalk, Buxton. In between the births of their children

and Bertha’s bouts of ill-health, the family occasionally went to Brighton

for holidays, where they stayed at Casa Ruge, at 7 Park Crescent, which

was the home of one of John’s closest friends Arnold Ruge. Ruge, a German

philosopher and political writer, had arrived in England in 1849 and to

Brighton in 1850 where he lived as a teacher and writer. In what was a

very sensible arrangement, while the Fretwells were in Brighton, the Ruge

family stayed in the Fretwell house in Hackney.

What business John was engaged in over this period is unclear but it must

have been connected with his wife’s family's business concerns. Even in

England, the machinations of the German relatives could not be avoided and

John had by 1871 resolved to sever all business connections with Herr

Heinrich Meyer. The latter stalled him with an offer of an agency in

America at some time in the near future, and in 1872 John, having arranged

for his sister Fanny to take care of his children, undertook his first

journey to America. It was apparently a successful visit and Meyer paid

John £1000 over an above the agreed sum. John was then sent to represent

Herr Meyer at the Vienna Exhibition of 1873. For John this was in many

respects the most interesting journey of his life, and it was at

Whitsuntide that year that he first visited the Unitarians of

Transylvania. In memory of his visit to Transylvania John published,

privately in 1902 (and apparently cheaply as the page cutting is very

crude) a small treatise, entitled ‘The Christian in Hungarian Romance’

dedicated to Dr. Maurus Jokai, a literary man whom John met while in

Hungary.

On the home front, the estrangement between husband and wife had reached

the point where in 1873 Bertha finally left John and returned to Germany

with the children. John’s sister Edith arranged for the packing up of all

the household effects. In all seventeen cases were made ready for

transmission to Bertha on the ship Virgo. The manifest document was signed

by Edith on 16 June 1874.

Household Effects Shipped to Hamburg

I Edith Fretwell of Ilkley in the County of York Spinster do solemnly

and sincerely declare as follows.

That I did on the tenth day of June last instant by the direction of my

brother John Fretwell (who is at present travelling in the United States

of America) cause to be transmitted by the Ship Virgo 17 cases ...

directed to Bertha Fretwell care of H C Meyer Hamburg - The following is

a list of the contents of the said seventeen cases.

Case BF1. 1 Bookcase, 7 Pillows, Spring Mattress, Carpet, 1 pair

blankets, Books.

BF2. 1 Walnut Table, 4 Chairs, 2 Blankets, 2 wool mats, 2 small

candlesticks, 1 ink stand, 3 albums, Letter Rack, Tool Box, Curtains and

Fringe, Bed and Table Linen, Showing Glass, Feather Bed, Counterpane,

Box of Photos, Books music etc, Childrens toys, Curtain, blankets, Music

Stool, Horsehair mattress, Bed covers, pillows.

BF3. Walnut Table, part of Whatnot, Marble Clock, Mattress, Foot stools.

BF4. Dining Room couch, 1 Chair, Marble slab, picture, part of whatnot,

Sliding table, 1 Leaf of dining Room Table, 1 Sheet.

BF5. Wash Stand.

BF6. 2 Easy Chairs, part of dressing table, 5 small chairs, painting,

part of sideboard, 1 sheet.

BF7. 1 Chest of Drawers filled with linen, ornaments and various

knicknacks, Crimson drugget.

BF8. Dressing table, Fancy cups and saucers, plate, two salt cellars.

BF9. Wash Stand, pictures, pole brackets and ends, Tea urn, knives and

forks, sugar basin, butter cooler, jug, Dolls tea set, Curtain holders

and tassels.

BF10. Writing table and work Table, pictures, mattresses, sheets.

BF11. Dining Table and leaves, 2 Easy Chairs, 4 small chairs, 5 curtain

poles, Spring mattress.

BF12. Side board, Table mats, Bracket, Glass Dishes, Globe of the World,

pictures, Dolls cradle, Toys, Butter dish, Candle cups.

BF13. Sofa, 2 arm chairs, picture, 1 small chair, marble slab or

washstand, Large photograph.

BF14. 2 Marble topped bedroom cupboards, ground glass lamp, globe,

Carpet etc.

BF1412. Books and pictures.

BF4180. Books etc.

That the whole of the goods therein contained consists of household

goods and effects the property of and used by my said brother in his

residence in England and sent by me at his request for the use of his

wife and family in Germany.

And I further say that I did on the twelfth instant cause to be sent

another case marked BF18 through Messieurs Elkam and Company addressed

as above consisting entirely of articles of silver used by my said

brother and sent for the use of his said wife as aforesaid. And lastly I

say that none of the said articles are of the nature of merchandise or

intended for sale but are solely articles used by my said brother or his

family. And I make this solemn declaration conscientiously believing the

same to be true and by virtue of the provisions of an act made and

passed in the Sixth year of the reign of his late Majesty King William

the Fourth entitled “An Act to repeal an Act of the present session of

parliament” entitled “an Act for the more effectual abolition of oaths

and affirmations taken and made in various departments of the state and

to substitute Declarations in lieu thereof and for the more entire

suppression of voluntary or extra judicial oaths and affidavits and to

make other provisions for the abolition of unnecessary oaths.

Edith Fretwell

at the Marion House in the City of London this